During the week, I wrote about the first few days of Auckland Writers Festival. While it’s still reasonably fresh in my mind — and despite being distracted by a Twitter feed full of #swf2014 — here are my notes and observations from the audience for last Saturday’s sessions at Auckland Writers Festival.

Saturday

Happy to leave Auckland’s Tiniest Hotel Room behind me for the day, especially for the day’s first session, A.M. Homes chaired by Paula Morris. I’d bought and started reading May We Be Forgiven the day before, after having it on my reading list for ages. The novel caught my attention when it won the 2013 Women’s Prize for Fiction; it’d been blurbed by Jeanette Winterson, and I’d watched this Winterson interview with Homes for the Guardian.

May We Be Forgiven is a ‘mid-life coming of age story’, and Homes described the character of Harry Silver unfolding as [her writing of] the book progressed. She was interested, she said, in the weave of fact and fiction. She cited playwrights of the 50s, 60s and 70s — including Pinter and Albee — as early influences. Homes was taught by the legendary Grace Paley and, asked about writing characters so different to herself (particularly writing male narrators), she cited Paley’s instruction to write ‘the truth according to the character’.

I love writing someone different from myself…[when I’m writing from the point of view of a male character] I eat more spaghetti, not so many carrots.

(That — the spaghetti and carrots quip — was the tenor of the session, strewn with humour from both Homes and Morris, one of my favourite writers festival chairs.)

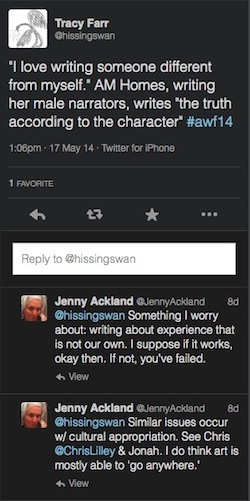

Jenny Ackland made a few excellent points via Twitter re this notion of writing someone different from ourselves:

Something I worry about: writing about experience that is not our own. I suppose if it works, okay then. If not, you’ve failed. Similar issues occur w/ cultural appropriation…I do think art is mostly able to ‘go anywhere’.

True on all counts. For me, though, having written a first-person narrator who’s an eighty-year-old bisexual heroin-smoking theremin player, I guess — like A.M. Homes — I embrace writing about experience that is not my own.

Homes talked about the traditional expectations of women’s writing (the domestic, the interior, the small — sigh), and that she writes outside or beyond those expectations, pulling the political, the social and the domestic together in her own work. She’s interested, she said, in

…the gap in the darkness between our public and private selves.

The next session featured another book that’s lingered long on my to-read list, Eimear McBride’s A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing (which won the inaugural Goldsmiths Prize, was shortlisted for The 2014 Folio Prize, and is shortlisted for the 2014 Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction). The session started with McBride reading from the first page of Girl — the perfect, necessary introduction to a prose style that is novel, strange, fragmented, and that Anne Enright described as ‘truth-spilling, uncompromising and brilliant…[and] on occasion, quite hard to read’.

McBride has described it, not as stream of consciousness, but as ‘stream of preconsciousness’. The prose in Girl is, she says

pre-formatting, before language, gut-reactive

Asked about the ‘Thing’ in the title — the jarring, even the shockingness, of that word — McBride said

There’s not a woman in the audience who doesn’t understand Thingdom.

Sex and sexuality are central in the book. McBride was seeking to find a new way to write sex.

There [was] no language for talking about sex that [was] not moralistic, judgemental, Catholic.

She’s interested in poetry for its licence, for the phenomenon that:

[Poetry, language] becomes bigger than the words on the page

Asked about the influences on her writing and her prose style, she talked about fellow Sligo local W.B. Yeats, and about the inescapability of comparisons with Joyce:

Molly Bloom is a wonderful piece of literature, but that’s not what goes on inside a woman.

She seems comfortable with the description of Girl as Modernist. Between Joyce at one extreme, and Beckett at another, she said

there’s plenty left in Modernism…post-modernism isn’t for everyone

She cited the play Crave, written by Sarah Kane, as an influence. It was hard to watch, and hard to read, she said, and

I didn’t know that women could own that kind of rage.

She finished up with a great soundbite quote:

“Girl” has little plot, but a very big story.

In the afternoon I went to a session that I was really looking forward to, but which fell a little flat in the flesh — perhaps I was expecting too much, or perhaps it was the inevitable result given the subject and the timing, in the week after the Australian budget was presented. In The Lucky Country?, Michael Leunig, John Marsden and Rod Moss, chaired by Felicity Barnes, were to ‘fathom’ Australia’s current state.

Michael Leunig said that, as a young person, he was baffled by the prevalent myths of Australia: ‘the lucky country’, mateship, Gallipoli. He understood that it referred to something, but

I didn’t get it.

Less than a week after the release of the Abbott government’s awful budget, it should have been no surprise to hear Leunig say that

The mood of Australia is pretty appalled. This budget is an expression of political philosophy imposed as an instrument of culture war. This alleged culture war is a matter of great grief to me. [Australia] doesn’t feel like my country any more.

John Marsden said that it was in the wake of the Tampa affair in 2001 that he first experienced

…not want[ing] to admit to being from a country that could be so brutal.

I came away from the session feeling flat, sad, angry. But I came away with one positive note: John Marsden recommended Chloe Hooper’s The Tall Man as compelling, so I’ll add that to the reading list.

Wearing my day job hat and my recovering scientist hat (just call me Johnny Two-Hats), next up was Science and the Big Questions with Jim Al-Khalili, hosted by Shaun Hendy. Shaun kept to the theme and kicked off with a big question:

How does the universe end?

Rather than taking useful notes on how the universe will end, all I seem to have recorded are a few neat quotes from Al-Khalili, peppered through the session, so here they are:

We want to demolish our theories, discover what’s wrong with them

You’ve gotta love this one:

Knowing all the answers is boring

Einstein, apparently, described quantum mechanics as

…spooky action at a distance…

I think my main reason for noting this was that it’s almost a quote from my novel. Here we go — on the second page of The Life and Loves of Lena Gaunt, observing how her body moves in the water as she swims, Lena notes:

Action at a distance; just like playing the theremin.

Next up, I was one of the record crowd filling the ASB Theatre for Eleanor Catton. As chair John Campbell said, there was ‘a spring in the national step’ when Our Ellie won the Man Booker. I confess: I have not read The Luminaries. I will, I will (when I find time and space to accommodate the great brick of it). I’ve read and heard Catton talk about it so often (I saw her at Perth Writers Festival, and again at NZ Writers Week in Wellington; her session at the latter talking with Max Porter, her UK editor, was fascinating), so I was pleased to find the session in Auckland engaging and interesting, even though it covered some ground I’d heard or read before. Of course, it was hard not to get swept away by the gushing enthusiasm of John Campbell leading the session.

Catton ‘dropped the A-bomb’ early on, launching into a discussion of astrology — it’s at the heart of The Luminaries — as a system, despite the fact that

My publishers in the UK have warned me against dropping the A-bomb too early, and losing the respect of the audience.

She aligned the systems of astrology (12 signs, seven planets) and music (chromatic scale with 12 pitches, diatonic with seven intervals).

Asking “Do you believe in key signatures?” is like asking “Do you believe in astrology?”

‘I value belief,’ Catton said, and

I value wonder and curiosity.

She talked about the importance of harmonic sympathy — a body responds to external vibrations to which it has a harmonic likeness — and relationality in The Luminaries.

There are people and places that bring out the best of us, and others, the worst.

As someone who’s a bit freaky about numbers and counts in powers of two when I can’t sleep (hint: it doesn’t work), I loved that the amount of the fortune in The Luminaries is 4,096 pounds (that’s two to the power of 12). Like Catton, I would’ve thought that was a clunkingly obvious number, and been surprised that people hadn’t noticed it and had a little giggle at her joke.

As someone who’s a bit freaky about numbers and counts in powers of two when I can’t sleep (hint: it doesn’t work), I loved that the amount of the fortune in The Luminaries is 4,096 pounds (that’s two to the power of 12). Like Catton, I would’ve thought that was a clunkingly obvious number, and been surprised that people hadn’t noticed it and had a little giggle at her joke.

She talked about the character of Emery Staines as the good heart of the novel.

It needs a good heart with all those [blackmailers and backstabbers] around.

In constructing or concocting or planning The Luminaries, she was influenced by the 1979 book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. She was interested in the notion of strange loops, and first considered (but soon abandoned) the idea of writing a novel that was causally circular. But ‘good ideas are born out of bad ideas,’ she said, and she moved on from causal circularity to the golden ratio structure that The Luminaries finally takes.

After strange loops, harmonic sympathy, and the preternaturally composed Catton describing herself as Socratic, I was relieved to hear that she got completely hammered after she won the Booker. On the morning after her win, facing twelve hours of interviews after no hours sleep, Catton did, she said, a so-so first interview. Her publicist, though, had thoughtfully scheduled a vomit break between the first and second interviews, after which break Catton bounced back and hit her stride.

On that note ended my Saturday at the festival. Up next, the final day of the festival: Alice Walker, Michelle de Kretser, the Gender Divides panel, Michael Leunig, and Patricia Grace.