I’m just home in Wellington after another festival for writers and readers, my third in four months (all years should be like this). I’ve written already about Perth Writers Festival (February) and New Zealand Writers Week in Wellington (March). Unlike these first two festivals, I wasn’t ‘performing’ at the most recent one, so it’s from the audience, not the green room, that I offer up these random notes from the first few days of Auckland Writers Festival 2014.

Thursday

I flew out of cold, wet Wellington wearing my too-heavy Wellington-weight coat; the relative warmth of Auckland still always surprises me even though, after so long, it shouldn’t. After I’d found somewhere in the Tiniest Hotel Room in Auckland to stash said coat (shoved into the bottom of the weirdly high cupboard, because I couldn’t — not even standing on the rickety folding chair — reach the rail to hang it), I wandered up through Albert Park to see Paula Morris give the University of Auckland Public Lecture Imperial World: the politics of book prizes. The venue was a rather shabby little lecture theatre in the Old Choral Hall, all fluoro lights and lino and that particular smell that old lecture theatres have (dust or chalk or god knows what, but it is very recognisable). The audience packed in, filling the place, and Morris (I hadn’t realised she’s soon joining the staff at UoA — lucky UoA) launched into a great lecture, her usual mix of wit and intelligent observation. I enjoyed it so much I forgot to take notes but, prompted by Annabel Smith:

I jotted down some notes later that evening. The blurb for the lecture promised a consideration of

whether the tastes of the UK market [should] still dictate what’s important in the international literary world

In her lecture, Morris noted that prizes like the Man Booker (which its website states “promotes the finest in fiction by rewarding the very best book of the year” and “is the world’s most important literary award”) and the newer Folio Prize (“open to writers from around the world” and “celebrate[s] the best fiction of our time, regardless of form or genre”), which tout themselves as being international in focus, and/or recognising the best writing in English, actually exclude anything and everything not published in the UK. Indeed, the focus tightens: they’re not just UK-centric, but strongly London-centric. These prizes represent the taste of London publishers. The most common setting is London, and English — not British — writers dominate the lists of past winners. Morris noted that in a sample she had made of data for recent overseas rights sales (for New Zealand books, I think, and perhaps only one publisher. I’m afraid my notes fail me…), while handfuls of sales were made into various European markets over the time period (a year?), only one single lit fiction title (anda single children’s title) sold into the UK market — so every other title remains ineligible for a prize like the Man Booker or The Folio.

Morris also noted that UK coverage of titles from New Zealand and Australia — if they get any coverage — is often snippy and condescending. She quoted one UK critic (and — I think she said — previous Man Booker judge) writing of Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries that it was “set in New Zealand, of all places”; and in a review in a UK paper, Christos Tsiolkas’The Slap was welcomed as “finally proof that Australia is interesting” (although these are both paraphrases from my scribbled notes — and I can’t readily find the reviews themselves to get the actual quotes).

Morris also talked about the Nobel Prize in Literature (“attempts have been made” to find worthy literature outside Scandinavia…), the Pulitzer Prize (unashamedly US), the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, the Neustadt Prize. She lamented the loss of literary prizes that aren’t centred solely in the northern hemisphere. The Commonwealth Writers’ Prize (awarded regionally for Best Book and Best First Book) and the Commonwealth Book Prize (for a first book) were disestablished in 2011 and 2014 respectively, and only the prize for a single short story remains in 2014; the Kiriyama Prize (for books about the Pacific Rim and South Asia) folded in 2008. She finished with a challenge — or perhaps it was just wishful thinking-out-loud — to establish a southern hemisphere “Nobel”-like prize for literature (calling all dynamite entrepreneurs?), to celebrate our writing, to refocus away from the north.

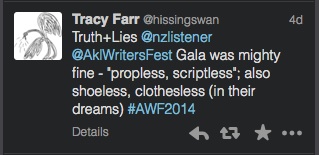

I hurtled down the hill to the Aotea Centre for the main kick-off event, the New Zealand Listener Gala Night — True Stories Told Live: Truth and Lies, featuring eight writers each delivering a seven-minute story “propless and scriptless”. The writers — Inua Ellams, Yasmine El Rashidi, Marti Friedlander, AM Homes, Sarah-Kate Lynch,Alexander McCall Smith, Irvine Welsh and, stepping in for the unable-to-make-it Lawrence Hill, Huw Lewis-Jones — were all great. I have no notes from the session, so I’ll simply taunt you, if you weren’t there, with those names, and you can imagine what you missed.

For the record, Huw Lewis-Jones was shoeless (the absence of a prop was his prop?); Sarah-Kate Lynch dreamt about doing the gig clothesless; and AM Homes’s first lie (sticking to the Truth and Lies topic) was about being scriptless (so she told us, pulling out printed pages of script as soon as she hit the stage).

Friday

Mostly, Friday was a writing day and night for me, some of it spent in the Tiniest Hotel Room in Auckland, much of of the afternoon in the cafe at the Auckland Art Gallery.

It wasn’t that there weren’t fabulous things on Friday’s programme at the festival; but I’d seen some of them (Elizabeth Knox on Wake; the dramatised reading of Damien Wilkins’ Max Gate; Jill Trevelyan on Peter McLeavey) at Writers Week in Wellington just a month or two ago, so I gave myself some writing time, instead.

In the evening, Irvine Welsh was excellent in his session Choose Life, in conversation with Noelle McCarthy. My minimal notes (again, I was just really enjoying the flow of the session) captured a few great lines. On his latest novel, The Sex Lives of Siamese Twins, Welsh said:

I [often] come up with a title first, then I think “what the fuck could this be about?”

McCarthy commented on the visceral in Welsh’s writing — the shitting and puking and drugging and all — and Welsh said it’s simply what’s universal, what we all experience as humans:

So much fiction’s all in the head…but we walk around in these weird bodies all the time…nobody shows that stuff, but I want to show it [in my fiction].

Welsh read not from his most recent novel, The Sex Lives of Siamese Twins, but from his 2012 book Skagboys, linked short stories that form a prequel to 1993’s Trainspotting. I found the reading — was it despite or because of its harsh language? I love a good c-bomb, me — unexpectedly beautiful. There was something about the poetry and rhythm of it that grabbed me, the wash of the accent that Welsh slipped straight into to read, both harder and softer than his speaking voice. There’s an extract from Skagboys that you can read on Welsh’s website. It’s NSFW (depending of course on where you W), but just have a look at the glory and strangeness of those words on the page. I can’t read it without vocalising it in a terrible cod-Edinburgh accent, reading it out almost-loud, under my breath. I haven’t read any Welsh for ages, probably since the 90s, but that session has prompted me to.

Welsh talked about living in the US, having moved there some five years ago.

In Britain, people only talk about the weather. In America, they only talk about food.

He didn’t feel that he could write a novel set in Chicago, where he now lives, because there’s such a weight and history of writing about Chicago and, as a newcomer, he didn’t feel he could match that or approach it. His latest novel, The Sex Lives of Siamese Twins, is set in Florida. He felt comfortable writing about Florida because, he said, everyone there is from somewhere else.

It was a great session, led really deftly by Noelle McCarthy (one of many excellent chairs/interviewers at the festival). I trotted back happily to the Tiniest Hotel Room in Auckland for another writing session, Welsh’s heroin and Irn-Bru menu translating (sad confession here) to a Nigel-No-Mates burger washed down with peppermint tea.

I’ll leave off there, with more to follow soon on my Saturday (AM Homes, Eimear McBride, Eleanor Catton) and Sunday (Alice Walker, Michele de Kretser, Michael Leunig, Patricia Grace) at Auckland Writers Festival.