A short story by Tracy Farr

Ellie’s having trouble finding rabbits for sale. ‘Not much call for them,’ the man at the supermarket tells her. ‘You could try the butcher in Island Bay,’ but she already has. And no, Bambi won’t do. It has to be rabbit. At Easter. She has to cook the Easter Bunny.

She finally finds them at Moore Wilson’s. The rabbits are wrapped in plastic, their headless bodies sleek and muscular. Wild rabbits, the sign says. That accounts for the sleekness. They’re posed on their polystyrene trays as if they’re leaping. They could be Burmese cats, lithe, skinned like this, just the meat, no distinguishing outside, no face or fur or paw or tail to tell you “cat” or “rabbit”.

Her hand is protected from the direct feel of the meat by its plastic wrap, but she can still feel the awful give of the muscle when she picks it up. She puts two packs of rabbit into her basket – plenty for her and Jeff, and his parents over for Easter, with enough for leftovers – then wanders the store checking off the rest of the ingredients from her list. Red onions, celery, carrots; basil, rosemary, flat leaf parsley: she’ll get those from the market on the way home. Balsamic vinegar she has at home, and red wine, but she needs tomato paste and tinned tomatoes, the good Italian ones. Olive oil of course, they never run out because they buy the big tins. She finds the good pasta on a rack near the flowers and picks up two packs of wide noodles, pappardelle, so she doesn’t have to make her own.

She’s cooking an autumny kind of rabbit recipe this year. Pappardelle sulla Lepre. When she’d first cooked the Easter Bunny they were living in Canada, where Easter was always springtime, so she’d made light, verdant meals then, new spring veges bursting off the plates. She chooses autumn recipes, appropriate to the season, now that she’s back home. “Eating this meal,” the recipe book says, “is like spooning up autumn.” Pappardelle sulla Lepre, she says out aloud, in the shop, talking to her trolley. Ellie loves Italian. She can’t speak it, but she loves to try to read it out aloud, loves the music of it off her tongue. Her voice always moves down when she tries to say Italian, sounds all deep and smoky and lovely, and she wishes she could sound like that forever.

It was an Italian recipe she’d cooked five years ago, too: the first year, in Vancouver, when the ritual of cooking the Easter Bunny started. The year she can’t make herself forget. Every Easter she’s reminded of it, and every Easter she tells herself enough, let it go. But every Easter, when she sees Jeff’s beloved face across the bunny from hers, it hits her again like a freshly-baited trap.

* * *

It was a perfect spring in Vancouver that year, everyone said so. Ellie bought thick yellow bunches of daffodils and jammed them, brimming, into two-pint preserving jars that she put on the windowsill in the living room, and next to their bed. Jeff was away for three months, working in Saskatchewan where the ground was still under metres of snow. By the time he was due back in Vancouver, Ellie’s spring would be over. She sent him emails, so that he didn’t miss out, to tell him what she saw – My first ever tulips I’ve ever grown outside are up!!! 🙂 – and then had to explain to him about forcing bulbs in the vege crisper at home in Auckland. Doesn’t get cold enough for them, she’d emailed, not like at your Mum’s in the sub-Antarctic, sorry, Invercargill. Miss you, XXXX E. Because he was absent, she thought of the flowers as blooming for her only, to cheer her, to keep her company. In later years though, the same flowers’ appearance would always, and only, remind her of his infidelity.

Her friends rallied around to distract her, to take her mind off Jeff’s absence. Marion and Alex saw her most days, popping around for this or that, asking her over for dinner, for drinks, to the movies. Marion and Alex could not conceive of anyone being anything less than miserable on their own. They made it their mission to keep Ellie occupied, despite her protestations that she quite liked spending time on her own. The best thing, Ellie told Marion, was being able to read in bed until as late as she wanted, without worrying about keeping Jeff awake.

‘Without him jumping you, you mean.’

‘Mad rampant cow, don’t be filthy.’

Alex’s birthday was on Easter Sunday that year and it was the Wednesday before, over mid-week, late-night, bottom-of-the-third-bottle wine, that Ellie offered to cook Marion and him dinner, to celebrate.

‘Your birthday’s always at Easter, every year since we’ve been here. Must be a moveable feast, eh, on the Church calendar.’

‘Yeah, it depends when the star appears in the sky and how long the wise men take to get here.’

‘That’s Christmas, Sweetie. Easter’s death.’

‘Oh Al, I know, I’ll cook you the Easter Bunny.’

‘God, how deliciously awful! In a chocolatey sauce perhaps, something italian-y-mexican-y-spanish? Or an ancient heathen recipe? Something Roman, with blood in the sauce.’

‘I love it!’ Marion snorted. ‘I can see it – perfect! – garnished with darling fluffy chickens and hand-painted eggs.’

And so Ellie’s part, her path was fixed: she would cook the bunny.

* * *

Ellie never needed to travel outside of West Side Vancouver to buy anything she wanted to cook. Jackson’s Meats, 4th Avenue, Kitsilano, always had rabbits. The butcher asked what she wanted, how many it was for and how she was cooking it, before he selected the meat and held it out to show her, seeking her nod of approval, her muttered mmm, perfect. They were never too busy to do butchery things for you: bone a leg of lamb, butterfly steaks, joint the rabbit.

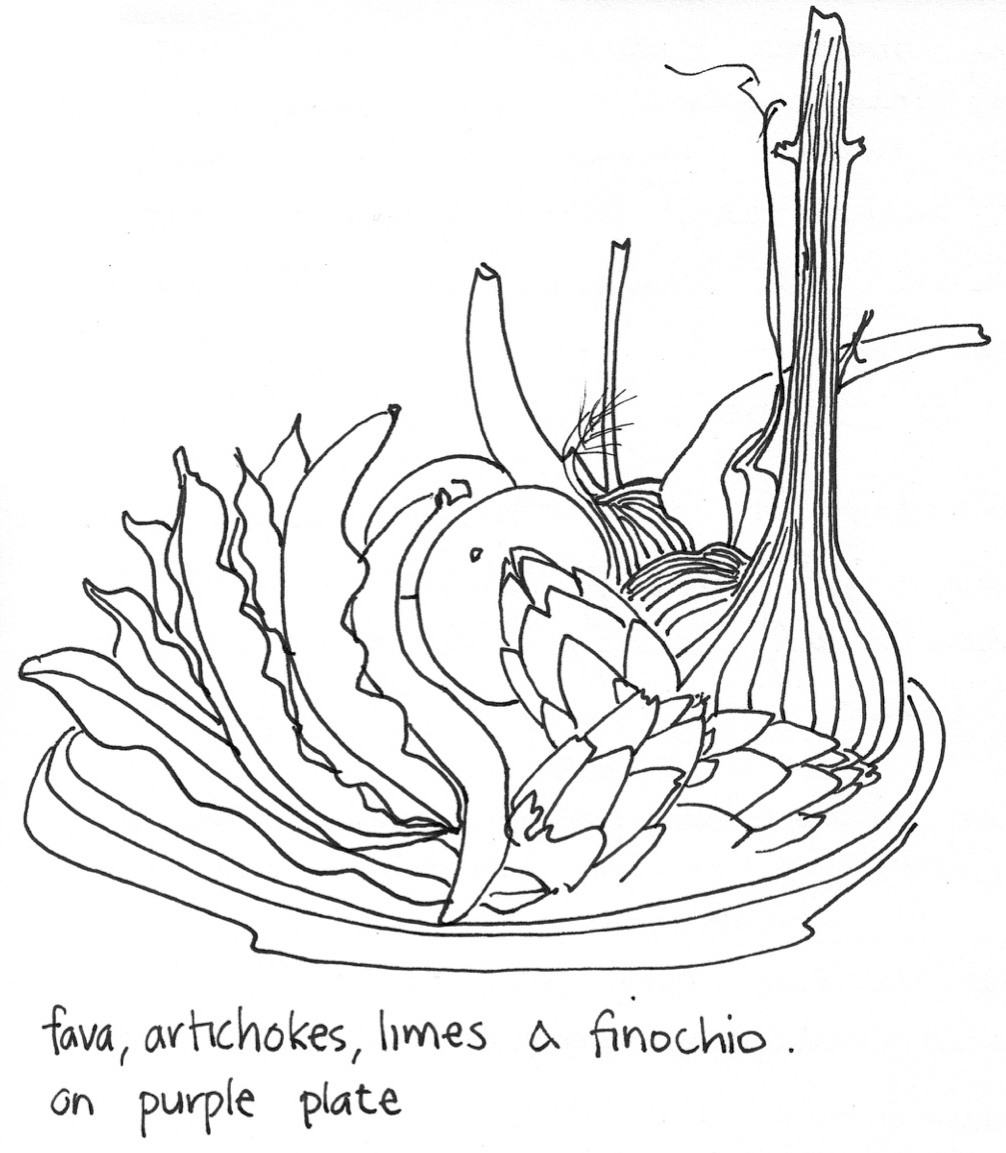

She’d gone home with a parcel of lean lovely rabbit parts and spent all Saturday evening cooking and drinking, listening to PJ Harvey CDs, the kind of music she never played when Jeff was home. Whining women’s music he called it. She thought he was just teasing. She seared the rabbit with chopped pancetta in olive oil, then braised it with crushed tomatoes, garlic, oregano and red wine. While it bubbled and perfumed the kitchen, and PJ whined loudly from the living room, Ellie arranged the vegetables on her purple platter, ready to cook them at the last minute the next day, to sauté them in olive oil then finish them with a steaming in lime juice. Fennel bulb, purple-tipped artichokes, furry fava bean pods, white asparagus, deep green limes, all on the old, cracked purple plate, but hiding the cracks so that all you saw was beautiful purple under the green. It was the most gorgeous arrangement of vegetables she’d ever seen in her life. Ellie wished Jeff was there so that she could hold it out to him, show him, tell him: Look what beauty I’ve made.

* * *

Marion phoned two hours before Ellie was expecting them the next afternoon, saying they were bored, they were ready to start drinking and they didn’t want to start without her, so could they come now, Sweetie, there’s a good girl, see you in ten. When Ellie opened the door to their knock, Alex handed her two heavy, oddly-shaped bottles.

‘Hi Honey. Poo wine, it’s wonderful. Tastes of the farmyard. Corkscrew in the kitchen?’

As they sat on the deck and drank, lapping up the last of the late afternoon sun, Ellie recited the words on the wine’s label. Rubino, Montepulciano d’Abbruzzo, Colle Secco, Cantina Tollo, Denominazione di Origine Controllata.

‘They’re beautiful enough to be from an opera,’ she said. ‘Poetry, pure poetry. Montepulciano d’Abbruzzo. By Giuseppe Verdi. Beautiful.’

‘Bella mia, I chantee the chianti for you!’ Marion started to sing the label to the approximate tune of the aria from La Traviata, in her terrible, gutsy voice, until Alex and Ellie drowned her out, shouting for her to stop. Alex poured more wine into her glass, then Ellie’s, then drained the bottle’s dregs into his own.

The wine was smooth and strong and tasted and smelled, as Alex had said, of the farmyard. Its smell was like manure, but a delicious, earthy, pleasing manure. By the time Ellie served up the rabbit, they were half way through the second bottle.

The rabbit melted off its tiny bones, creamy polenta sopped up the braising liquid. The wine was perfect with the food; even the asparagus and artichokes couldn’t spoil it, as if its earthiness could take anything. Bread mopped up sauce, wiped fingers. They grazed on the salad of arugula and radicchio, already full but still eating, slowly. The second bottle of wine hadn’t lasted nearly to the end of the rabbit, and Ellie had brought out the good bottle of Mondavi Pinot that she’d bought to go with the meal. Alex opened a bottle of shiraz to keep them going through the salad. By the end of the shiraz, Ellie was looking through the cupboards for liqueurs. Marion put on Ellie’s only Van the Man CD, Tupelo Honey, cranked the volume as high as it went, and they sang and danced until Marion had broken two glasses, Alex had spilled his Cointreau down Marion’s front, and Ellie had thrown up in the planter box on the balcony.

They collapsed back into the chairs around the dining table, staring at the candlelit still life of rabbit carcass and daffodils.

‘Narcissus,’ Alex said, plucking a stem from the jarful on the table, twirling it in his fingers. ‘Daffodils are Narcissus. Narcissuses. Narciss-eye. Narciss-ee.’

Ellie reached across the table and grabbed the daffodil from him, then stuck it in her mouth like a Spanish dancer with a rose. Olé, she said through teeth gritted around the stem. She relaxed into her chair, head back, teeth still gently clenched over the daffodil’s stem, then slowly raised both arms until they formed a steep V. She clicked her fingers — right, left, then right once more, imagining castanets — then spat Olé again around the daffodil, grinning.

Marion leaned forward over the tabletop, head in close to stare at the flowers. ‘Are they poisonous? Daffodils? I read it, I know I read it. Rats dig them up and eat them. Probably think they’re potatoes.’

Ellie dropped the stem from her mouth onto the table, stumbled into the bathroom, cupped water in her hands and drank and spat, again and again, to try to get rid of the taste of poison. She looked in the mirror, pushed her face up close to the glass, poked out her tongue and stared, looking for poison taint. There was nothing she could see, but the imagined bitterness still wouldn’t wash out of her mouth no matter how much water she rinsed with. Even when Marion and Alex finally left to stagger the two blocks home, and Ellie fell into her spinning bed, she could still conjure an image of taunting, bright, cheery daffodils marching through her body, slowly poisoning her.

Ellie nursed her hangover the next morning like a complicated lover, staying in bed and clutching it to her, wanting it gone, wanting the night never to have ended. She was still in bed, sipping a cup of peppermint tea, when Jeff phoned at lunchtime. The words he told her mingled with the tastes of peppermint and vomit and daffodil and rabbit and manure so that forever after, when she tried to remember with any sort of exactness what the words were that he’d said, all she remembered was the feeling of poison. She thought he told her he loved her, after he’d told her the poisoning, unfaithful words, but she could never be sure, when she tried to remember.

It was late afternoon by the time Ellie made it out of bed, after hours of crying, a little sleeping, and half an hour retching over the empty icecream tub she’d put by her bed the night before, just in case. The living room was filled with the fug of rabbit remains and wine dregs. From their jar in the middle of the table, the daffodils shone at her like an insult. Ellie scooped the flowers onto the platter with the rabbit bones, breaking the stems to fit the plate. She carried the lot into the kitchen, dumped it in the garbage, then walked back to the living room and hit play on the stereo. She sank onto the sofa as if the music hit her, and cried her pain again, and again.

* * *

Queuing with her basket full of rabbits and veges and pasta at the checkout at Moore Wilson’s, Ellie spots passionfruit, 80 cents each. She leaves her trolley in the queue, goes over to the passionfruit and picks them into a bag, choosing the heaviest fruit. They’re the perfect ending for her autumn Easter dinner.

She never used to see passionfruit for sale in Vancouver, so by the time they left to come home to New Zealand she’d almost forgotten they existed. When they were on the plane back home – after the poison had subsided, after the kissing and making up, when it was finally starting to feel as if they were moving past it – somewhere between LA and Auckland when the copious free g&t started to wear off, they had played the old interviewing game they used to play when they first met, pretending they didn’t know each other, hoping to surprise or be surprised by their answers.

‘Are you happy about returning to New Zealand?’ she’d asked Jeff, teasing him with the formality of the question, but wanting to know, wanting him to know she meant with me.

‘Yeah,’ he’d said, ‘actually, I am.’ He’d held her hand then, all his warmth focused through his fingers into hers. ‘What are you looking forward to most? What have you missed?’

‘Passionfruit,’ she’d said, surprising herself. ‘Passionfruit on a vine, so you can’t eat them fast enough, so you take three for lunch every day and slurp them with a spoon. And then you get sick of them, you have so many.’

Ellie remembers spending the summer she turned nine staying with her Gran in Warkworth, just the two of them together, while Ellie’s mum and dad stayed in Auckland squabbling about when the new house would be finished. They did the traditional tour of the garden the first day she arrived, Ellie with a glass of lemonade with iceblocks in it, Gran with a glass of beer because the sun was over the yardarm. Gran showed her the flowers on the passionfruit vine, told her why they’re called passion flowers.

‘Look. Five petals, five sepals. They’re the ten apostles who stayed faithful to Our Lord. And this circle of hairs, that’s the crown of thorns Our Lord Jesus wore on the day of His death. And this purple on the flower, purple for His Passion.’

Ellie remembers thinking that passion was what the big girls and boys did up the back at the school disco, and not wanting to ask Gran what Our Lord Jesus was doing at the school disco, thinking it must have had something to do with That Mary Magdalene. So it wasn’t until she went through a heavily religious year at fifteen that Ellie finally understood what Gran had been talking about. The Passion of Christ. The suffering and death of Our Lord Jesus Christ, who died for our sins so that we might be redeemed.

She’ll make fruit salad with these ones. Or squeeze them over icecream, like she used to do at Gran’s. Or sit in the kitchen by herself before Jeff gets home and eat them all with a teaspoon, the little black seeds sliming down her throat like eyes in nectar.

* * *

Walking from Moore Wilson’s to where she’d parked the car, just down the street, Ellie sees graffiti on a wall, quite high up, well above her head height. It catches her eye because the letters are so small, neatly made with a thick black marker. She stops to read it, resting her shopping bags on the ground. EASTER: an historical fact. Jesus Christ died for you on a Roman Cross. She wonders what a Roman cross is. She wonders if the writer means to establish fault on the part of the Romans. And then she thinks, well, he didn’t die for me, pappardelle or no pappardelle.

But it moves her, that graffiti, to think in churchlike ways she never thinks herself capable of any more, big concepts like resurrection, and redemption. She ponders someone dying for someone else’s sins. She thinks of sacrifice, and selflessness. Then revenge and retribution. She thinks how amazing it is that people have been remembering the death of that one man for two thousand years. Or maybe it’s not so amazing: there are some things you just never forget, like your gran’s birthday, or how to spell your own name, or the exact purple of the bedspread you got when you turned ten. Or the taste of a deep, soul-scarring infidelity.

And she whispers to herself, in a voice passionate as cheap incense in a teenage bedroom: I will never forgive him. Thank Christ he came back.

Editions/availability

An abridged version of ‘Passion’ was produced and broadcast by Radio New Zealand in 2005. It’s replayed occasionally (often around Easter) on RNZ.

Image (and finocchio misspelt as ‘finochio’) by Tracy Farr.